About

WHAT IS BRUNEL'S SWIVEL BRIDGE?

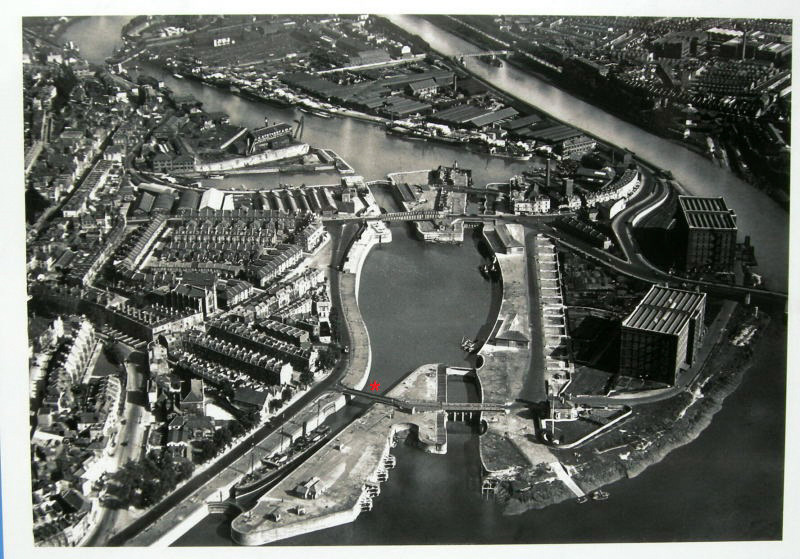

Isambard Brunel’s innovative rotating bridge was originally built to carry a road across his new Entrance Lock to Bristol City Docks. It was built in 1849 in the same dockyard as the SS Great Britain and by the same firm. It still survives today, next to the 1872 Entrance Lock where it provided an essential crossing until made redundant by the Plimsoll Swing Bridge, commissioned in 1968.

The deck is 33 m (110 ft.) long, weighs about 70 Tonnes, and, although derelict, can still rotate.

The bridge is a Grade 2* listed national heritage asset and on Historic England’s Buildings At Risk Register, where its condition is described as ‘very bad’.

WHY IS THE SWIVEL BRIDGE IMPORTANT?

It is remarkable evidence of Brunel’s thinking. The innovative design clearly reveals Brunel’s creativity at a time when he was developing new ideas for longer, stronger bridge spans. Some design features didn’t work, but those that did were copied elsewhere both in the UK and abroad. This is a pioneering structure, designed at a time of competitive creativity in bridge- building, and a key part of Brunel’s legacy.

It is unique. The Bridge is the oldest rotating bridge in the world, older than the Clifton Suspension Bridge, and the only early moving wrought iron bridge to survive intact.

It was built in Bristol. It was constructed in the same dockyard as the SS Great Britain and by the same firm, George Hennet & Co.

It is complete. Despite being severely rusted in places, the structure is substantially complete and can still rotate.

It is an exceptional example of the best of Victorian technology. The design is strong but economical and lightweight, constructed over a short period, but to an exceptionally high standard of workmanship.

It is constructed of wrought iron. This traditional hand made material is no longer made. It was jointed using

white-hot rivets, hammered manually, a process no longer used in construction.

It was technologically innovative. The Newcastle firm Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd. supplied a jigger mechanism to rotate the deck using hydraulic water power alone - originally the Bridge had been operated manually. This jigger equipment survives intact, demonstrating the technology that led directly to the oil hydraulic systems used widely in engineering solutions today.

It is historically significant. The Bridge is recognised by its national Grade 2* listing, putting it in the top 4% of

the UK’s most important heritage assets.

WILL THE BRIDGE HAVE A USE WHEN RESTORED ?

It will provide an essential crossing over the Entrance Lock, needed now, and even more so within the proposed Western Harbour scheme. It will form part of the walking and cycling routes, which the Western

Harbour project team are championing, and become an essential link between cycle routes north and south of

Cumberland Basin. This will also provide a new route for long-distance running events and access to Ashton Gate Sporting Quarter.

With this practical function, it will also support Bristol Council’s Climate Emergency Action Plan, One City Plans and Transport strategies.

Currently the only passage is over the lock gates themselves. Many feel unsafe on these minimally guarded walkways and they are tricky for cyclists, scooter users and those with walking or other mobility difficulties. For wheelchair users, prams and pushchairs, the lock gate walkways are completely impractical, whereas the restored Bridge would offer a safe and usable route.

The Bridge will be operable by harbour staff with a one-button system, alongside the existing lock gate controls.

Crucially, the Bridge will also provide a focus for the many heritage assets in the Western Harbour area and

act as a catalyst for their conservation and interpretation. This will form an essential part of preserving the heritage appeal of this end of the harbour as it is developed.